As Bantu communities became adapted to specific environments, so interactions with more distant communities grew less and their languages and material cultures diverged.

|

| Photo: Stu Westfield |

By the middle of the first millennium BC, Bantu & Iron culture had infiltrated into the Kilimanjaro and North Pare region in north east Tanzania and southern Kenya. Probably assimilating the pre-existing coastal fisher-pastoralist population. As the eastern Bantu became acquainted with coastal and open water navigation they continued south and then into the hinterland of Dar es Salaam.

|

| Later chief Meli as a boy standing next to Dr. Hans Meyer visiting the Meli family before his Kilimanjaro ascent - wiki commons |

|

| North Pare mountains Credit: C rocca854 at English Wikipedia, Public domain, Wikimedia Commons |

By the 11th Century, the Bantu language had differentiated into distinctive dialects, including proto Taita-Chagga spoken by the creators of Maore ware in North Pare, Kilimanjaro and Taita. The inhabitants of North Pare subsequently developed into the proto-Chagga. The descendants of whom would become the focal point of social and economic reorganisation of the Kilimanjaro region in later centuries.

Chagga Expansion

The typical Bantu social organisation was a clan headed by a hereditary clan chief. The proto-Chagga evolved a new kind of position where the chief was not tied to a single clan but ruled over a territory inhabited by different clan affiliations. This development coincided with a the introduction of the Indonesian banana to highland agriculture, yielding a production advantage. Which set off the Chagga expansion into the heavily forested eastern slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro and beyond.

The surplus crops led to the creation of formal markets. Pastoralists brought hides and the few remaining hunter-gatherers contributed to the trade with honey and wild animal skins. The Wageno tribe of the north Pare became tied to this trade in their role as specialist smelters of iron and tool makers.

16th to 18th Century

From 1500 the emergence of chieftaincies and structured political organisations led to a trend towards a tributary mode of production. The distinct ethnic groups which we know today evolved, linguistically and culturally, in the interior of Kenya and Tanzania.

Salt from Lake Eyasi and iron were important trade items in central Tanzania. In the late 1700's the Mamba chiefdom became the iron working centre for the Kilimanjaro region. From the road that wound its way around the slopes of Kilimanjaro, the Ngaseni traded huge beer pots.

The Chagga were still relatively isolated from the coast. Meanwhile the Swahili City States had risen under the rule of Arabian, Egyptian and Perisan traders with a network that extended as far as India and China. There is no record of Arab or Swahili penetration of the interior before 1700 and there is no significant collection of imported objects yet found at any interior site.

It was the Miji-Kenda and then the Akamba caravans which supplied many of the coastal settlements with products from the interior such as ivory, gum, honey, beeswax, grain, foodstuffs and wood for building dhows. In return for exchanging goods from the interior, the Miji-Kenda (who themselves were largely cultivators of millet, rice and fruits) obtained salt, beads, cloth and importantly, iron.

|

| Tanzania, modern composition. |

19th Century and Kilimanjaro

The German missionaries Johannes Rebmann of Mombasa and Johann Krapf were the first Europeans known to have attempted to reach the Kilimanjaro. Although initially, reports of a glaciated peak on the Equator were dismissed as preposterous.

This morning, at 10 o'clock, we obtained a clearer view of the mountains of Jagga, the summit of one of which was covered by what looked like a beautiful white cloud. When I inquired as to the dazzling whiteness, the guide merely called it 'cold' and at once I knew it could be neither more nor less than snow.... Immediately I understood how to interpret the marvelous tales Dr. Krapf and I had heard at the coast, of a vast mountain of gold and silver in the far interior, the approach to which was guarded by evil spirits. - Johannes Rebmann's diary entry of 11 May 1848

|

| Photo: Stu Westfield |

Interestingly, by this time, Rebmann found the people in the Kilimanjaro region to be so actively involved in far-reaching trading connections that a chief whose court he visited had a coastal Swahili resident in his entourage. Chagga chiefdoms traded with each other and with the Kamba, Maasai and Pare in the immediate surrounding area as well as with coastal caravans. Many chiefdoms had several produce markets largely run by women, just as they are today.

The Wachagga Today

Today's Chagga are the third largest ethnic group in Tanzania. Their relative economic wealth still derives from the fertile volcanic soils of Kilimanjaro and Mount Meru along with successful traditional methods of agricultural terracing and irrigation. Banana, yams, beans and maize are grown for domestic consumption and local trade. But also, the area is internationally famed for its high quality Kilimanjaro single origin Arabica bean coffee.

|

| The famous Kilimanjaro Native Co-Operative Union Cafe in Moshi https://kncutanzania.com/the-union-cafe/ |

Despite oppression during colonial rule, Chagga men and women have rebounded within an independent Tanzania as prominent contenders in modern politics and local government. Many young Chagga work as clerks, teachers, administrators, and run businesses. Women in rural areas are also generating income through activities such as crafts and tailoring. The Chagga are renowned for their sense of enterprise and strong work ethic. Which is no doubt why many also find employment as professional guides and porters on Kilimanjaro.

.JPG) |

| Assistant Guide, Richard, sporting a bold line in Kili mountain fashion |

Climbing Kilimanjaro

Mount Kilimanjaro was first summited on 6th October1889 by Hans Meyer, and Austrian climber Ludwig Purtscheller with a local guide, Yohani Kinyala Lauwo. Although, we cannot be certain that an African was not there first, as local folklore warned people from ascending too high. On the mountain lived malevolent spirits that would kill those who came too close, twisting and blackening their limbs. Stories which sound like they were describing frostbite.

|

| Head Guide, Sabas |

For my second time on Kilimanjaro, our local Chagga guide was Sabas. Named after the Swahili word saba, as he was the seventh child in his family. Our route was one which allowed for the best acclimatisation, ascending through the Lemosho Glades, then onto the Shira Plateau. Working our way around the west flanks, over the Barranco Wall then establishing at Barafu Camp before the summit bid up the screes to Stella Point and then a short hike around the crater rim to Uhuru Peak

It was on this trip that I met Simon Mtuy, in a vignette that plays back in my mind like the opening sequence of David Lean's 1962 film Lawrence Of Arabia.

I awoke as the thin rays of dawn illuminated the canvas of my tent. It was early and the air was still cold, but there was no hurry, breakfast was not for another half hour. My breath condensed to vapour as I pulled on my boots, unfolding myself as I emerged, in search of coffee. In the clear skies above, the sun was just starting to warm the air, slowly encroaching on the remaining frost laying in the shadows on the ground. Looking across the Shira Plateau, emerging through the shimmering heat haze, a figure, running towards camp. A local guy, had to be, top off, tracksuit bottoms and trainers. I stood in awe at his athleticism, at 3500 metres above sea level. He closes the distance, smiles, we greet. A brief "habari za asubuhi," and "nzuri sana." He stopped at the collection of tents behind ours, where his group had camped. It was later in the day, while taking a rest near Cathedral Point that we met again. Sabas seemed to know him quite well and understandably, he was a bit more talkative. Sabas introduced us to Simon Mtuy, who at the time, held the record for the fastest ascent of Kilimanjaro....

Tanzania, the people, mountains, wildlife and experiences has given me so many cherished and happy memories. There seems no better way than to conclude this story than with the following words:

Stu Westfield

Ranger Expeditions

Sources:

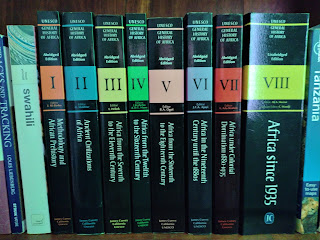

UNSECO General History Of Africa Vol III

Ch 22: The East African Interior. C. Ehret, University of California, Los Angeles

UNSECO General History Of Africa Vol IV

Ch 19: Between the Coast and The Great Lakes. C. Ehret, University of California, Los Angeles

UNESCO General History Of Africa Vol V

Ch 27: The interior of East Africa: The peoples of Kenya and Tanzania 1500-1800 W.R. Ochieng, senior lecturer, Moi University, Eldoret, Kenya.

https://www.science.org/content/article/early-africans-went-bananas

https://archive.archaeology.org/0609/abstracts/bananas.html

https://www.worldhistory.org/Swahili_Coast/

Kilimanjaro To The Roof Of Africa. Audrey Salkeld pub National Geographic 2002