African history, from a popular British perspective, is a selective story. No sooner have anthropologists discussed the origins of humans, then it's how quickly those humans could get out of Africa. Except for dwelling upon the enigmatic Egyptian pharaohs, millennia of culture is set aside and there's a giant leap forward to the European scramble for Africa, slavery and colonial rule. Omitted, are rich periods of history, the ebb and flow of great African civilisations, technologies and people.

|

| Photo credit: thebantutribe.weebly.com |

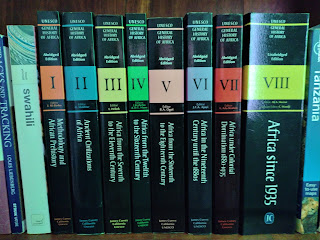

In 1964 the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) started a project which sought to redress this imbalance. Essentially, telling the story of the continent, by Africans with an African perspective. The outcome was a series of volumes, culminating in the General History Of Africa, Vol 8, Africa Since 1935, published in 1993. Currently, there are plans to extend the series by three more volumes.

|

| Photo: Stu Westfield |

Journalist and president of SOAS (London School of African Studies), Zeinab Badawe used the GHA to inform her series 'History Of Africa', televised in 20 parts, originally on BBC World News, but now available on You Tube.

History Of Africa - Zeinab Badawi - Links to full series

In this blog we explore one of world history's greatest but overlooked movements of people, accompanied by technological and cultural change. One so rapid, it has been called by some historians 'an explosion!'

This was the Great Bantu Migration.

Origins of the Bantu

If we draw a line from south Nigeria to the East African coast, modern Bantu speaking peoples now comprise 90% of the population south of this line. There are over 2000 Bantu languages spread across East, South and Central Africa, with common terms and grammar. Linguists have traced the timeline of this divergence back to around two to three thousand years ago, to a source area we now call the Nigerian-Cameroon border.

Chronology of the Bantu is also supported by looking at the shape and decoration of artefacts. A method known as typography. From common forms, a strong regional diversity and stylisation developed among Bantu groups who had settled following their migratory radiation.

The end of the Stone Age in Africa

Archaeological studies of later pre-history have shown that peoples were living at different stages of technological development contemporaneously in different parts of Africa. There was no single end to the stone age. Many hunter gatherer communities were still using stone age technology right up to the first millennium of the Christian era. While developments such as agriculture and iron usage had become established elsewhere for several hundred years.

We can compare this to Mesolithic Britain populated by bands of hunter, fisher, gatherers. Meanwhile, Neolithic agricultural practices and animal domestication were spreading across the European continent from the Near East.

Iron and the 'Explosive' Bantu Expansion

There are several theories as to the origins of iron working in West Africa, from introduction via trade routes to indigenous development associated with the Nok people. What is more certain is that iron was already in use by the migrating Bantu people and that the beginnings of arable agriculture occurred with the first appearance of iron technology. Linguistics supports this, as words associated with iron working were in use before the migration and diversification of the Bantu language.

It is clear that iron made possible new methods of higher yielding agricultural practices, producing an excess, facilitating population growth and trade. Iron also enabled faster clearing of forest and efficient tilling of the land. The early Bantu migrants sought out areas similar to from which they came and were familiar with: Wooded or forested lands, near to rivers, which had sufficient rainfall for yam based agriculture.

Over the next three thousand years the Bantu vectored along rivers in their canoes and forest trails. The expansion was not linear but spread in pulses and different directions. The early migrations (3000 to 1000BC) went into the forest lands south to the Congo river and east into the Great Lakes region.

Around 500BC the migration entered East Africa and by 500AD the Bantu had reached southern Africa. Most of the migrations were complete, circa 1000AD. So, while the migration timeline of thousands of years hardly sounds explosive in a modern global context, for the period it was an incredible rate of population movement for a single origin culture in pre-history.

So what happened to the Bronze Age?

Unlike the British pre-history sequence (Mesolithic - Neolithic - chalcolithic - bronze - iron), there was no specific bronze age in sub-Saharan Africa as technology progressed from stone to iron.

The earliest copper usage comes from Mauretania between the 9th and 5th centuries BC. Culminating in some of the finest examples of bronze work made in 16th century Benin. Although evidence of iron smelting to 2000BC pre-dates the earliest bronze and copper metalwork in West Africa.

|

| Benin Bronze. Photo: Stu Westfield |

And the cows?

Bantus were agriculturalists not pastoralists. However, cattle keeping does pre-date iron in East Africa, spread by the Central Sudanic (Cushitc) speakers living in North Uganda and Tanzania (near Lake Victoria). Generally the Bantu moved into spaces which were unexploited or unsuited to the cattle herders. It is possible that the incoming Bantu learnt about domesticated sheep and cattle from these herders.

And the indigenous populations?

The Bantu expansion into the Congo basin encountered forest dwelling pygmy tribes, also known as African rainforest hunter gatherers. Who's distinctive diminutive stature and physiology were well adapted to the dense forest environment. Genetic studies have shown that the Mbenga and Mbuti pygmies are direct descendants from Middle Stone Age peoples of Central Africa.

|

| Nyamwamba river valley, Uganda |

Scholars have characterised the Bantu expansion as fast and purposeful. And as colonsiation rather than conquest. At first, the impact would have been small, even inconsequential, in the vast forest and so the pre-exiting population was not over run. However, forest clearance for agriculture was completely incompatible with indigenous hunter gatherers way of life.

Over time, a burgeoning Bantu population would have limited the local hunter gatherers natural food resources. This led to assimilation of many pygmy groups. Others managed to retain their independence by living in areas which supported game, but not agriculture, trading skins with the neighboring Bantu.

The Batwa of Uganda are traditional forest dwellers, who lived by hunting and gathering. Remarkably, for thousands of years their homeland, the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest was left sufficiently intact by the bordering Bantu communities.

|

| Photo credit: C Dawson |

This all changed in 1992 when the forest was made a national park. In order to protect the mountain gorillas the Batwa were evicted. As is common with many indigenous tribes in modern times, their rights were poorly represented. Displacement and discrimination continue to have adverse impacts on their health, culture and welfare.

In 2021 the PBS Newshour reported that the Batwa population of Uganda has an average life expectancy of just 28years and 40% of children do not survive to the age of 5.

|

| Photo credit: C Dawson |

Some hope for the Batwa is capitalising on their relatively recent co-existence in the forest environment, creating employment as tour guides, cultural experience leaders and trekking porters. This is a far cry from actually living in their ancestral range and comes with the distinct possibility of reducing their skills to a tourist show. It's an imperfect choice now faced by many first-nations the world over.

The job offer of a lifetime

Back in 2012, I was leading a trek in the Rwenzori and had a final couple of nights at the Kampala Backpackers hostel before the flight back to Blighty. My group was on a school's expedition and we had journeyed through Rwanda into Uganda, with a moving, enlightening and amazing range of experiences to reflect upon.

The proprietor of the hostel and Rwenzori Trekking Services was the charismatic John Hunwick. John and I had shared a couple of brief phone discussions during the trip, mainly to confirm a few logistical details and arrangements. I liked his straight taking, he was businesslike but also very generous with his local knowledge.

Relaxing in the Kampala hostel, my group had time on our hands as the flight had been delayed a further 24 hours. John and I struck up several conversations, I got to know how he came be in Uganda and founding the Backpackers Hostel and RTS. He had some great stories. He also seemed to like how I'd conducted the expedition and with some on-the-hoof forward planning, circumvented a few local difficulties without any drama. Then he suddenly came out with a jaw dropping offer...

"Stu, I need a guy like you to help run the hostel and treks in the Rwenzori. Come and work with me."

"Blimey, John, I'd love to. But I have a wife and two dogs back home."

"Come back with them!" John was quite insistent.

Sadly, I could never had taken him up on the offer. Although well into her remission and at the time reasonably able, Dolores still had the lasting effects of cancer to deal with. An outpost in Uganda, really wasn't the place to be taking her to. However, the recognition that John's offer inferred was good to hear.

Here's a few words from John, his work, vision and thoughts on progress in Uganda...

John Hunwick Interview & Show Notes - Gorilla Highlands Podcast

Conclusions to Part 1

The European historical view, presents Africa as somewhere humans left and then more recently returned to colonise. This notion conveniently ignores the history of the continent in the intervening thousands of years. Indeed it fits a narrative of colonising 'empty lands' as a policy without consequence to people. Where people were present they needed to be converted to conform to European religious and political values. Here we tread a line between judging the past with today's values and acknowledging that some actors of the time most certainly set aside their probity in order to treat other human beings so appallingly.

The Great Bantu Migration story, is but one illustration that people in Africa were thriving, innovative and sophisticated, long before European influence. The evidence paints a picture of loose collections of independent but interacting communities. As Bantu communities became adapted to specific environments, so direct interactions with more distant communities grew less and their languages and material cultures diverged.

On a local scale, three way exchange was mutually beneficial between the Bantu, hunter-gatherers and pastoralists. Within the Congolese economy Bantu speaking peoples traded in fish, salt, cloth, mats and baskets.

The Bantu diaspora went on to built some of the Great African Kingdoms, such as Great Zimbabwe founded in the 9th Century and Mapungubwe, in the 11th Century. Long distance trade routes spread cross the continent and incredibly, the Great Zimbabwe network reached as far as China.

In the next parts of the story, we shall look in more detail at other tribes and cultural groups, particularly in East Africa. The Hadza hunter gatherers, the Wachagga whos identity stems from the Bantu migration and the Maasai who arrived later.

I'll leave you with a short film from my first visit to the Rwenzoris in 2007 as a client, before I became an expedition leader. Indeed, it was this experience and the people I met that set me on the path to becoming a Mountain Leader. Looking at the film now its is perhaps a little cliched, but it was put together for fun and made with a heart full of appreciation for Uganda.

Sources

UNSECO General History Of Africa Vol 2

Ch 21: M. Posansky, historian and archaeologist

Ch 22: A.M.H. Sheriff, Lecturer, University Dar-es-Salaam

UNSECO General History Of Africa Vol 3

Ch 22: C.Ehret, linguist, University of California, Los Angeles

The Chronological Evidence for the Introduction of Domestic Stock in Southern Africa - C Britt Bousman, African Archaeological Review, Vol. 15, No. 2, 1998

A brief history of Botswana - Neil Parsons, Botswana History Pages

Sub-Saharan Africa, Early Bantu Migrations - Barratt, Long Branch School, New Jersey

https://thebantutribe.weebly.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment