SCOTLAND’S IRON AGE BROCHS

Over the past few years, I have travelled to the Isle of

Mull and archipelagos of Orkney and Shetland exploring and documenting evidence

of our Neolithic stone age ancestors in short films and earlier blogs. In a

world where everything was made from wood, plant materials, antler, bone and

stone, the richness of their cultures and cosmology has been astonishing.

|

| Neolithic-Bronze Age archaeology at Jarlshof, Shetland |

However, I also found amazing structures from the next

revolutionary period: The turbulent, tribal and somewhat disturbing

developments that came with the Iron Age.

|

| Stu at Mousa Broch, Shetland Islands |

IRON AND A NEW REVOUTION

The iron age brought an end to the closing chapter of the

stone age. People had previously learnt to smelt copper and alloy it with tin

to form bronze. But cast bronze is brittle and its practical usage was limited.

The form of items made in the bronze age closely mirrored those of the

preceding Neolithic. Archaeologists have speculated that the purpose of these

artefacts was principally ceremonial or ritual.

Another disadvantage of bronze is that copper and tin are rarely

found anywhere near one another. And, though copper is easy to find, tin is a

relatively rare metal. The collapse of trading structure at the end of the

Bronze age forced early metallurgists to experiment with iron. Iron itself is

not much harder than bronze, but it was discovered that adding about 2% carbon

produced steel.

Steel could hold a better edge and made for superior tools

which further revolutionised agricultural efficiency. Steel also made better

weapons for people to intimidate, injure and kill each other. Communities

responded by making defensive structures, such as the hill forts of southern

England or the Broch roundhouse buildings found throughout Atlantic Scotland. Archaeological

examination of skeletons from this time shows terrible cutting and slashing

wounds, leading to conclusions of strong tribal identities within the

population.

|

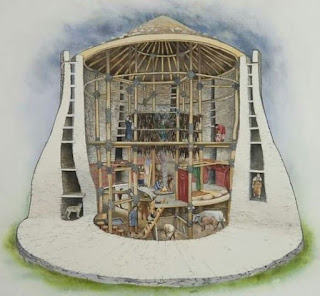

| Broch visualisation cross-section |

Brochs' close groupings and profusion in many areas may

indeed suggest that they had a primarily defensive or even offensive function.

Some of them were sited beside precipitous cliffs and were protected by large

ramparts, artificial or natural. Often they are at key strategic points.

|

| Defensive use of steep sided creeks at Midhowe Boch, Orkney |

Generally, brochs have a single entrance with bar-holes,

door-checks and lintels. There are mural cells and there is a scarcement

(ledge), perhaps for timber-framed lean-to dwellings lining the inner face of

the wall. Also there is a spiral staircase winding upwards between the inner

and outer wall and connecting the galleries.

|

| Spiral staircase, Mousa Broch |

Brochs vary from 5 to 15 metres (16–50 ft) in internal

diameter, with 3 metre (10 ft) thick walls. On average, the walls only survive

to a few metres in height. An example of a broch tower with significantly

higher walls is Mousa in Shetland.

The Shetland Amenity Trust lists about 120 sites in Shetland

as candidate brochs, while the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical

Monuments of Scotland identifies a total of 571 candidate broch sites

throughout the country.

|

| Distribution of Brochs |

Radiocarbon dates for the primary use of brochs (as opposed

to their later, secondary use) still suggests that most of the towers were

built in the 1st centuries BC and AD. A few may be earlier, notably the one

proposed for Old Scatness Broch in Shetland, where a sheep bone dating to 390–200

BC has been reported.

GURNESS BROCH – North West Mainland Orkney

In common with about 20 Orcadian broch sites include small

settlements of stone buildings surrounding the main tower. There are

"broch village" sites in Caithness, but elsewhere they are unknown.

|

| Gurness Broch |

Settlement here began sometime between 500 and 200 BC. At

the centre of the settlement is a stone tower or broch, which once probably

reached a height of around 10 metres. Its interior is divided into sections by

upright slabs. The tower features two skins of drystone walls, with

stone-floored galleries in between. These are accessed by steps. Stone ledges

suggest that there was once an upper storey with a timber floor. The roof would

have been thatched, surrounded by a wall walk linked by stairs to the ground

floor. The broch features two hearths and a subterranean stone cistern with

steps leading down into it (resembling the subterranen chamber at Mine Howe, Tankerness). It is thought

to have some religious significance, relating to an Iron Age cult of the underground.

|

| Gurness Broch |

The Gurness Broch's location is facing Midhowe Broch on the

opposite shore of Eynhallow Sound. Perhaps as a highly visual projection of

tribal strength. But also, the building materials for each of these brochs are

easily taken from the rocky flagstone outcrops on each shoreline. Thus readily

enabling increases in size and complexity of the broch settlement structures, as well as projection of tribal strength.

|

| Natural building materials on the shore at Midhowe Broch |

MIDHOWE BROCH – Rousay, Orkney

Midhowe Broch is situated on a narrow promontory between two

steep-sided creeks, on the north side of Eynhallow Sound. The broch is part of

an ancient settlement, part of which has been lost to coastal erosion. The

broch interior is crowded with stone partitions, and there is a spring-fed

water tank in the floor and a hearth with sockets which may have held a

roasting spit.

|

| Midhowe Broch |

The broch is surrounded by the remains of other lesser

buildings, and a narrow entrance provides access into the defended settlement.

The other buildings seem to have been built as adjacent houses, but later in

the site’s history they were used as workshops, and one of these buildings

still retains its iron-smelting hearth

MOUSA BROCH – opposite Shetland mainland, located by the

sea.

|

| Mousa Broch |

|

| Remains of Burraland Broch |

|

| Mousa Broch |

Although there was much argument in the past, it is now

generally accepted among archaeologists that brochs were roofed, perhaps with a

conical timber framed roof covered with a locally sourced thatch.

|

| Mousa Broch interior |

Mousa Broch continued to be used over the centuries and is

mentioned in two Norse Sagas. Egil's Saga tells of a couple eloping from Norway

to Iceland who were shipwrecked and used the broch as a temporary refuge. The

Orkneyinga Saga gives an account of a siege of the broch by Earl Harald

Maddadsson in 1153 following the abduction of his mother who was held inside

the broch.

CLICKIMIN BROCH – Lerwick, Shetland

|

| Broch island on Clickimin Loch |

Originally built on an island in Clickimin Loch, it was

approached by a stone causeway. The broch is situated within a walled enclosure

and, unusually for brochs, features a large "forework" or

"blockhouse" between the opening in the enclosure and the broch itself.

|

| Clickimin Broch blockhouse |

OLD SCATNESS BROCH – Sumburgh, Shetland

Located close to arable land and a source of water (some

have wells or natural springs rising within their central space).

JARLSHOF BROCH – Sumburgh, Sheltland

|

| Remains of Jarlshof Broch after coastal erosion |

The remains at Jarlshof represent thousands of years of

human occupation, and can be seen as a microcosm of Shetland history. In a

similar story to the discovery of Skara Brae in Orkney, a storm in 19th century

washed away part of the shore, and revealed evidence of these ancient buildings

and one of the most complex archaeological sites in Britain.

|

| Complexity of Jarlshof site, pic Scottish Heritage |

Buildings on the site include the remains of a Bronze Age

smithy, an Iron Age broch and roundhouses, a complex of Pictish wheelhouses, a

Viking longhouse and a mediaeval farmhouse.

|

| Pictish wheelhouse at Jarlshof |

Most brochs are unexcavated. Those that have been properly

examined show that they continued to be in use for many centuries, with the

interiors often modified and changed, and that they underwent many phases of

habitation and abandonment. The end of the broch building period seems to have

come around AD 100–200

INSPIRED BY STONE

Our stone age crafts made in Hayfield are inspired by the human journey from paleolithic beginnings to the Viking era. Ranger Expeditions also offer challenge trekking days and discovery themed walks guided by local Mountain Leaders.

No comments:

Post a Comment