Situated on and around Kilmartin Glen is an astonishing concentration of Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments, including standing stones, a henge, numerous cists and a linear cemetary comprising five burial cairns.

Indeed, there are so many that in trying to see as much as possible the visitor might flit from one to the next. Thereby missing a sense of place, the interrelation of monuments and how they fit within the environment.

|

| Image: Stu Westfield |

Anyone that has ever journeyed on a lower Nile cruise will understand. The week begins as a feast for the eyes, as you experience the wonder at what the pharaohs and ancient Egyptian society achieved all those millennia ago. By the end of the trip, it's all too easy to feel 'all tombed out'. To preserve the initial magic, its helpful not to cram too much in, but to pick and choose. Also to look away from the obvious eye-catching attraction of the monuments and enjoy the view.

With a relatively short time available, I took the same approach to Kilmartin Glen. Selecting a handful of accessible sites, each with a particular interesting feature or reason to visit and see.

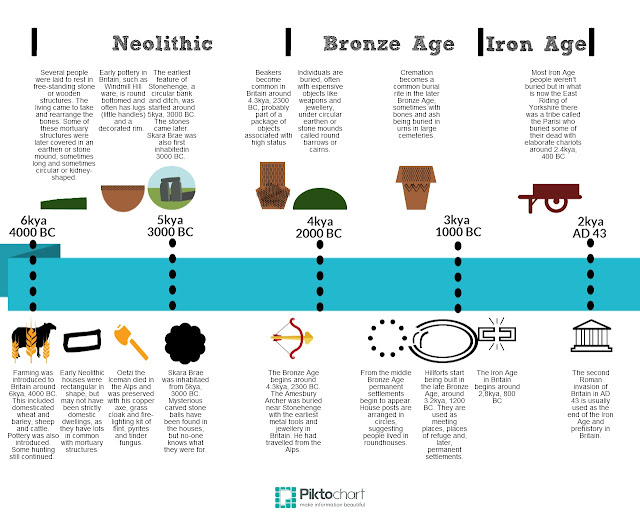

We will also be looking at evidence of how monument style, culture and funerary practice changed within Kilmartin Glen from the late Mesolithic to Bronze Age. So it's worth sharing a timeline for additional context. It's important to remember when referencing any timeline to look at both the date and location. The Neolithic and Bronze age transitions, often called 'revolutions' occurred through migration of people, ideas, culture and portable items.

|

| Credit: Kim Biddulph - Prehistory blog |

Dunchraigaig Cairn

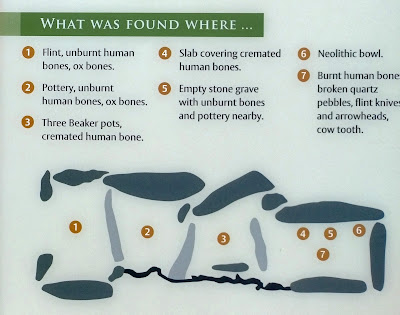

This was my first stop. Just across the road from a visitor car park. It was unusual in that it has three cists inside, each with a different style of inhumation. (A cist is a burial chamber made from stone).

|

| Image: Historic Scotland visitor information board |

The cist to the east contained only cremated bones. The central cist contained a full-length body on top of its cover slab, with cremated human bones inside and below this a layer of rough paving which revealed yet another body, in a crouched position.

|

| Image: Stu Westfield |

But the third cist, on the south-east side was the most unusual. Dug directly into the ground, lined with drystone cobbled walls and capped with a massive stone, it contained the remains of up to 10 individuals, some cremated and some not. It also held a whetstone, a greenstone axe and a flint knife.

|

| Image: Stu Westfield |

While cairns often became the burial place of more than one individual, it is rare to find so many individuals in one cist. Bronze Age cist burials, like this one, were usually reserved for one person – multiple burials are more often seen in Neolithic tombs. (source Historic Scotland)

|

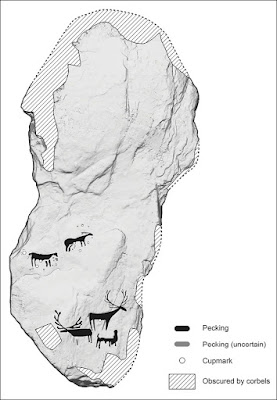

| Credit: Guillaume Robert, University of Edinburgh |

At the time of visiting, the south-east cist had been sealed off to protect a chance rediscovery of deer carvings on the underside of the cap stone. Dating back to the early Bronze age, deer carvings are rare. Most rock art dating from this this period in Scotland is cup and ring marks. While prehistoric animal carvings are known in Europe, this fresh discovery in Britain offers new insight and challenges assumptions about culture and migration in this period.

Nether Largie Standing Stones

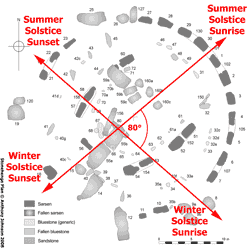

Stone circles and standing stones are an ongoing topic of research and debate regarding their significance in terms of celestial alignments. Stonehenge, for example, has long since been associated with the summer solstice sunrise.

|

| Stonehenge alignments: Source Stonehenge Tours |

But archaeologists now believe that the diametrically opposite alignment to the mid-winter sunset was of primary importance, signifying the sun's rebirth and a new cycle of farming activity.

Greater discussion of this topic is given in the Stonehenge Tours blog:

https://www.stonehenge-tours.com/blog.Astronomical-Alignments-at-Stonehenge.html

|

| Image: Stu Westfield |

Research on the the Nether Largie set supports interpretations as both a solar and lunar observatory. The stones mark where the moon rises and sets at key points in its 18.6 year cycle. They also align with the midwinter sunrise as well as the autumn and spring equinox sunset.

|

| Image: Stu Westfield |

The Nether Largie stones were erected about 3200 years ago. However, three of the stones are decorated with cup marks and rings, which typically date from 1500 years earlier. Indicating that the standing stones were probably cut from previously decorated rocky outcrops, like those at Achnabreck. A site which we shall return to later.

|

| Image: Stu Westfield |

The slanted top of the tallest stone is a feature which we have seen in circles on Arran and Orkney. The pleasing aesthetic of this cleaving line as it points to the sky is undeniable. With such a detailed level of planning and intent for the purpose of the stones it would be remarkable if this characteristic was not particularly sought out in the selection of raw materials.

Temple Wood Stone Circles

Walking among the various sites in Kilmartin Glen, they all share a significant sense of being rooted in the landscape. The surrounding hills, nearby river and flat valley bottom are all in common with other ancient sites I have seen in Arran and on the Isle Of Mull. These monuments are a projection of status, cultural identity and perhaps power. Acting as an influence upon the behaviour and compliance of the local habitants. As well to impress, even intimidate, visiting tribespeople causing them to think:

'Here is a well organised community. Look at their splendid interactions with the sky. Their reverence for those which have gone beyond to join the ancestors. Our journey to this place is significant and meaningful. We should be friends with them. We wish to make our contribution to the celebration of ancestors. Our people could also trade with them. We should seek joining of relations for our sons and daughters. Together we will be strong.'

Or they may have coveted what they saw and with duplicity and guile, overcome and placed themselves in the ruling seat.

|

| Southern circle. Image: Stu Westfield |

On first appearance, the Temple Wood stone circles have more in common with a kerb cairn. Like the Moss Farm Road cairn seen at Machrie Moor on Arran. The larger southern circle, has an obvious cist structure at its centre. Both have rounded cobbles graded to size as an infill. With larger cobbles added as an outer ring on the southern circle.

|

| Southern circle cist detail, dating to 4000 years ago. Image: Stu Westfield |

Archaeology had given us a 2000 year timeline, during which the circles went through several phases of use. Beginning 5000 years ago with a timber circle on the northern site, which was soon replaced with stones and the second southern circle was built. Phosphate analysis, shows that about 4200 years ago a cist just outside the southern circle was used as a burial. The inhumation accompanied by a beaker and arrowhead.

|

| Temple Wood circles timeline. Historic Scotland information board. |

The two cairns built inside the southern circle, around 3300 years ago, have small stone 'false portals' at right angles to their kerbs. Both these fake entrances face southeast, towards the midwinter moonrise. (Source: Historic Scotland information board).

|

| Northern circle, with a splash of spring bluebell colour. Image: Stu Westfield. |

A similar false portal cairn is located near to the stone circle at Lochbuie on the Isle Of Mull. In our film Neolithic Mull we describe the lunar impression an infill disc of fresh, gleaming white cobbles would have upon those seeing the tomb, before it had weathered into the landscape.

Link to Ranger Expeditions' Neolithic Mull film (false portal kerb cairn at 3min 14sec):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2gTPH8KER0s&t=592s

Nether Largie South Cairn

|

| Image: Stu Westfield |

This Neolithic chambered tomb is one of the earliest monuments in Kilmartin Glen, build around 5500 years ago. Typically chambered tombs were originally used as bone repositories, possibly after the body had been excarnated (de-fleshed) in the open.

|

| Historic Scotland information board. |

Maybe with the aid of animals such as sea eagles, other birds or dogs, if the totemic evidence in contemporary Orcadian tombs can be translated to Kilmartin Glen. The bones were then disarticulated, sorted and interred within the chambers.

|

| Chamber entrance. Image: Stu Westfield |

|

| Chamber. Image: Stu Westfield |

However, later ritual practice, is evident at Nether Largie South. Around 4300 years ago people reused the tomb for burial, also placing pots and flint arrowheads with the dead inside the chamber. Then, a few generations later in the early bronze age, they re-modelled the tomb. Converting it into a circular cairn like the others along the valley bottom. Two stone cist graves were added. (source: Historic Scotland, information board)

|

| Nether Largie South tomb contents. Source: Historic Scotland |

|

| Cist structure. Image: Stu Westfield |

Achnabreck Rock Art

Just 8 miles south from Kilmartin Glen is Achnabreck, the site of some of the most prolific and impressive prehistoric rock art in Britain.

|

| Image: Stu Westfield |

The use of landscape at Achnabreck appears to be very different to the Kilmartin context. The monuments at the glen draw people in from the surroundings. Whereas the Achnabreck location is on high ground overlooking the valley between Lochgiphead and Cairnbaan. The cup and ring marks seem to project outwards.

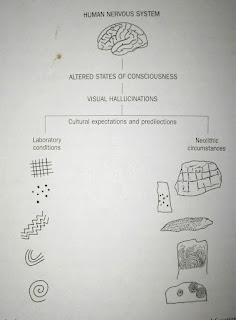

The use of psychotropic substances in rites of passage is common among indigenous communities around the globe. It's not a great stretch to presume that our ancient ancestors used shamanism to induce trance and altered states of mind during ritual activities. They certainly would have had an intimate knowledge of which plants were good to eat, which were toxic and which could be used to produce hallucinogen like effects.

|

| Image: Stu Westfield |

The designs at Achnabreck were created between 5500 and 4500 year ago, during the later Neolithic. They look the most remarkable when the sun is low. Among the most remarkable are seven concentric rings 1 metre across on the middle outcrop and the double spirals on the upper outcrop. Some designs seem to run in parallel to the cracks and fissures in the rock, which are naturally aligned to the midwinter sunset. (Source: Historic Scotland information board)

But what to these symbols mean? Why did people take time to carefully peck these motifs into solid bedrock? And why was it necessary to repeat the exercise numerous times? The lower Achnabreck surface contains 83 symbols, while there are more than 100 on the upper outcrop.

|

| Image: Stu Westfield |

More than 3000 panels of rock are have been found in Scotland, while thousands of prehistoric carvings are occur along Europe's Atlantic fringe. The common symbols hint at shared knowledge and beliefs among people that created them. (Source: Historic Scotland information board)

There have been many theories as to their meaning. Some more outlandish than others and quite a few which are frankly ridiculous and belong in the pages of science fiction comics. One of the more plausible which is backed up by experimental reconstruction, is that the symbols are an artefact of the mind, created when either under the influence of, or remembering, a shamanic type experience.

|

| Image: Stu Westfield |

We have explored this concept previously when looking at the the markings etched on a mesolithic pendant from Star Carr, Yorkshire.

http://stuwestfield.blogspot.com/2020/05/044-recreating-star-carr-mesolithic.html

Mesolithic hunter gatherers and Neolithic farmers had different ways of life and culture. There is a possibility that shamanic etchings are a cultural carry-over, but this presumes the Neolithic revolution absorbed and integrated with hunter gatherer societies. The DNA evidence does not always bear this out. Comparative studies of ancient British hunter gatherer skeletal DNA with Neolithic remains, show that the immigrant continental Neolithic farmers replaced the indigenous hunter gatherer populations.

Interestingly DNA analysis of the next major cultural change - the arrival of the Beaker People, which signified the end of the Neolithic and beginning of the bronze age - showed that more than 90% of Britain's Neolithic gene pool was replaced by people related to the Beaker people of the lower Rhine at the start of the bronze age.

|

| Credit: D Lewis-Williams & D Pearce |

However, to us, the enigma is what did these symbols represent in the consciousness and cosmology of Neolithic people? Monument structure and styles, funerary practice and portable artefacts can lead us to speculation and a best guess. We are looking back as if through a frosted window and we may never know is what rituals, rites of passage or ceremonies, prompted the creation of these symbols.

The Stone Age Re-Crafted In Hayfield

I have recreated a range of stone age motifs from the ancient past. Inspired by the distant paleolithic, through the continental and British Neolithic, bronze age and into the Viking era. Some pieces are fashioned into tea light holders, all are distinctive and highly decorative.

https://rangerexped.co.uk/index.php/stone-age-crafts/

Stu Westfield

Ranger Expeditions - Trek Leader

Guided experiences & challenge walks

Peak District 3 Peaks Challenge

Edale Skyline Challenge

Kinder Scout Sunrise Breakfast Experience

Kinder Scout Supermoon Special

Kinder Scout Winter Wonders

Ranger Ultras

low-key, big-enjoyment, great-value, trail-running

No comments:

Post a Comment